Today I figured I’d explain the current name of this blog, and, in the process, expand on some concepts I touched on in my last post.

To start, we’ll have to take a look at narratives as a whole. Essentially, every narrative is actually impacted by the media through which it is delivered. Even if the story is entirely identical, the medium will leave it’s own distinct character. For example, An audio book, read aloud by an individual, will have a specific tone and pacing that would be left ambiguous in its written form.

We can break down all forms of media into these basic properties, and see how stack up against each other. As noted above, audio books, radio and other audio media have a defined tone over a written piece; TV and film, in turn, add a visual component that brings it’s own set of advantages over radio. However, for every advantage that comes with a more advanced or complex medium, there is a corresponding disadvantage. It’s easy to assume that TV is wholly superior to radio in conveying information, since you have an audio and visual component in TV, as opposed to just audio. However, if the goal is to create a tight, focused narrative, that extra component may just get in the way. In radio, you only have the words of the speaker to focus on, without a screen full of images that distract from the message. It is for this reason that I generally prefer radio/podcast news over videos: TV news stations love to throw flashing graphics at you, when I would much prefer to just hear what’s going on in the world.

When looking at works within a given media, the best examples of narratives will leverage the strengths of their chosen media whilst mitigating the impact of their weaknesses. One excellent example of such leverage can be found in the use of color in Schindler’s List. Given that the vast majority of the flim is entirely shot in black and white, the girl in red becomes a moment of striking contrast for the viewer, and we become fixated on her, much like Schindler himself. While this girl in red does exist in the original book, her depiction there comparatively lacks weight, as there is simply no way in which a novel can generate color contrast in such succinct and unmistakable terms as can a film. Overall, We can think of color as being one aspect of many that film (as a medium) wields as a unique advantage.

For a videogame, their unique feature (and consequently, their greatest advantage and flaw) is interactivity. Through interactivity, videogames receive a host of unique properties to implement in their stories:

- They are the only media that a consumer can not only give up on, but actively fail at.

- They are the only media where it is possible, or even expected, to unintentionally miss content.

- They are the only media that take effort.

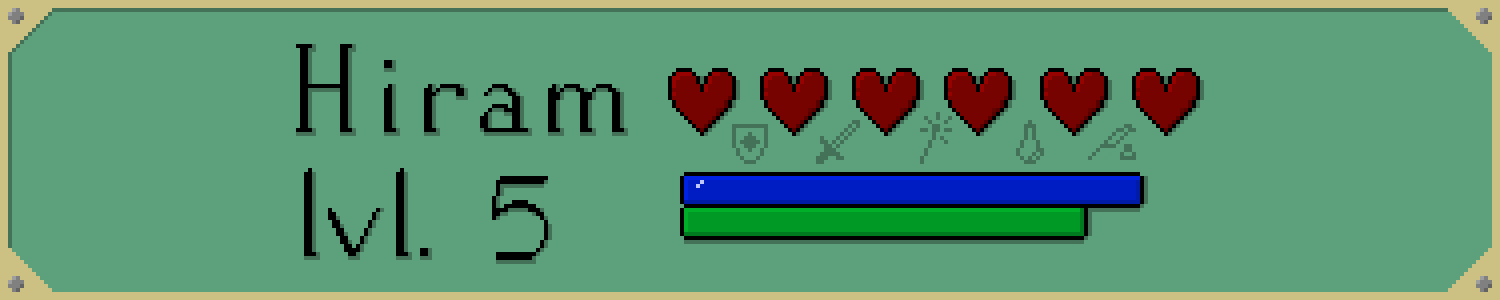

I’ll certainly be exploring how these properties are utilized (with varying degrees of success) in games, but that will be the topic of many more articles to (hopefully) come. For now, on to my title. In many games, the first moment of interaction, the first moment wherein the player is given agency, is when they are asked for a name. The player is given complete freedom to make this choice, and their decision is injected throughout the game. True, a name may have little to no effect on the progression of the game, but it certainly has an impact on the mindset of the player. Many, including myself, name their character after themselves, be it for immersion, wish fulfillment, or plain laziness. Others turn their name into a recurring gag—a slur, innuendo or pun to be referenced in perfect deadpan by the unassuming game. And others yet turn their chosen name into an entire persona, exploring each game through a set of entirely new and unique eyes. Videogames are, fundamentally, a series of choices, and there are virtually no choices in any games that give as much agency to the player as this very first moment.

Next Time: a game I didn’t like. And probably one or two I did like, for comparison.